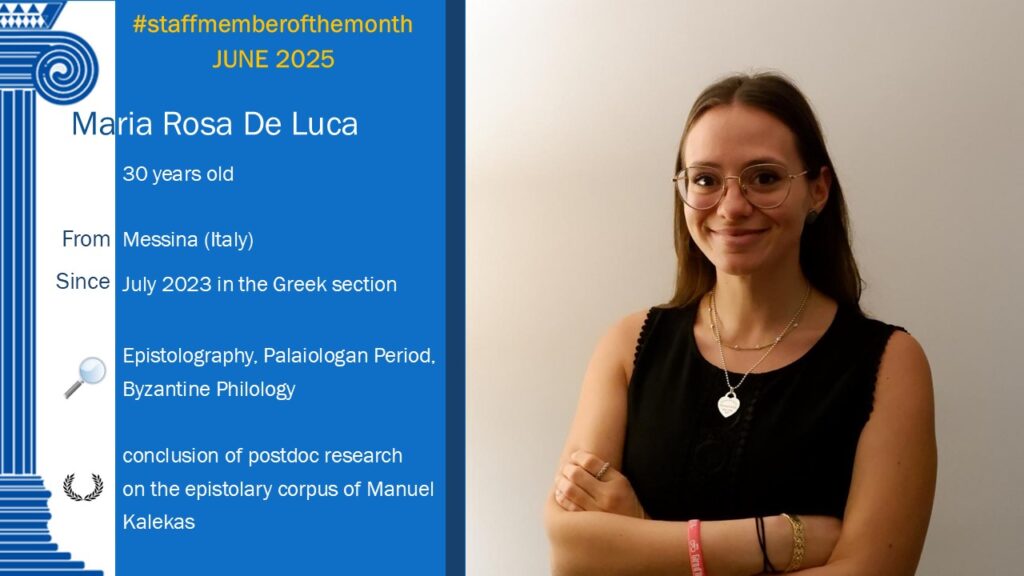

Maria Rosa served as a postdoctoral researcher within the ERC project MELA, during which she focused on the epistolary corpus of Manuel Kalekas. With her project now concluded, she reflects on her time in Ghent and the many reasons she found it so rewarding.

Hi Maria Rosa! You joined our Section two years ago — hard to believe it’s been that long! Now that your contract has concluded, what do you think you are going to miss the most?

It’s incredible to think that two years have passed already — time really does fly! What I’ll miss the most is, without question, the friends and colleagues I’ve met here in Ghent. Our office was a truly special space — not just a workplace, but a lively hub where disciplines met and minds connected. We were a wonderfully diverse group: experts in Indo-European, Spanish, Byzantine and Germanic linguistics, in astronomy, and even in Byzantine poetry — a combination that might sound unusual at first, but which created an ideal environment for creative dialogue. Our spontaneous conversations — often beginning as casual chats over coffee — frequently turned into stimulating exchanges that influenced our respective projects in unexpected and productive ways.

That daily intellectual cross-pollination, the sense of shared curiosity, and above all, the warmth and humor of the people around me — these are the things I’ll carry with me and miss dearly.

Kalekas lived during a time of intense political, theological, and cultural conflict — a context that’s deeply reflected in his letters, which offer a unique window onto the ideological and emotional landscape of late fourteenth-century Byzantium.

You are a Byzantinist and a post-doc inside the MELA Project. Can you tell us more about your work?

Yes, absolutely! As a Byzantinist within the MELA project, my research focused on the epistolary corpus of Manuel Kalekas, one of the most fascinating intellectuals of the late Byzantine period. Kalekas lived during a time of intense political, theological, and cultural conflict — a context that’s deeply reflected in his letters, which offer a unique window onto the ideological and emotional landscape of late fourteenth-century Byzantium.

My work centered especially on the linguistic dimension of his epistles. I analyzed the stylistic and syntactic features of his Greek, identifying those elements that are distinctive of the so-called Palaiologan phase of Byzantine Greek. This included studying his use of rhetorical strategies, lexical choices, and morphosyntactic constructions — all of which help us understand not only his individual voice, but also the broader evolution of Byzantine prose in an era of East-West exchange and internal turmoil.

I’ve developed a very personal routine here in Ghent for unwinding after work. Most days, I’d go for a walk along the canals — something I never got tired of. (…) During those walks, I often went in search of a good Italian-style espresso — which, as many Italians in Belgium can confirm, is easier said than done!

How do you like to relax after a long day of brain gymnastics — Netflix, naps, or just staring blankly at a wall sipping coffee?

I’ve developed a very personal routine here in Ghent for unwinding after work. Most days, I’d go for a walk along the canals — something I never got tired of. The city has a way of calming you down with its quiet water, narrow streets, and ever-changing skies (yes, even the grey ones!).

During those walks, I often went in search of a good Italian-style espresso — which, as many Italians in Belgium can confirm, is easier said than done! After much trial and error, I came to the firm conclusion that the best espresso in town was not in any café, but right in our building: the one brewed in the Greeks’ kitchen on the first floor! That became something of a ritual — a moment of connection, caffeine, and conversation that perfectly capped off even the most intense day of research.